The mirror-stage in a broken hall

There is a version of me that smiles too easily. He is pleasant, articulate, and (I think) difficult to dislike. He listens well, offers helpful advice, moderates himself in company, smoothes the edges of silence, fills the gaps. I've watched him at work during the day. He's useful, convincing, even warm at times. I'm not ashamed of him, but I no longer trust him.

What unsettles me is not that he exists, but that he sometimes precedes me. He appears in doorways before I've decided to enter them, extends his hand while my own still hesitates at my side. This doppelgänger with my voice but none of my hesitations, none of the weight that sits behind my eyes. People greet him before they greet me. And I, still arriving behind my own expression, find myself slipping into his shoes as if they had never left my feet. I follow the conversation trails he's already blazed, inhabit the promises he's made on my behalf. By the time I've fully arrived, he has already committed us both to a version of reality I'm still considering, still tasting for truth. The gap between us narrows with each passing year, and sometimes I wonder if one day I'll catch up only to find he's become me entirely, or worse, that I've become him.

I've been thinking about Richard III. Not the history, not the bones under Leicester car park, but the man as Shakespeare staged him: charming, sardonic, venomous with grace. A man who weaponises performance, wears deformity as a costume, and plays the villain so convincingly that even he begins to believe the script. His soliloquies are mirrors. He tells the audience clearly who he is and who he will become, and still, no one sees him until it's too late, not even himself. There is a scene late in the play where Richard begins to unravel. He is alone, haunted by ghosts, suddenly unsure of who is without the mask. "Is there a murderer here? No– yes, I am." The role collapses in on itself. The act that sustained him begins to consume. I think about that a lot.

Sometimes I stand before bathroom mirrors and practice my own performances — the casual laugh, the interested nod, the sympathetic tilt of the head — wondering if I too am crafting something that will eventually hollow me out. We all curate versions of ourselves, but Richard's tragedy lies in forgetting which version came first. His deception becomes so complete that when the ghosts arrive, those spectral reminders of authenticity, he has no centre to return to. The crown sits heavy on his head, not because of its weight but because he has become nothing beneath it. I wonder how many masks we can wear before we forget the face underneath, how many roles we can play before the script becomes our only reality, leaving us, like Richard on Bosworth Field, crying desperately for a horse, for escape, for anything solid in a world suddenly turned to shadow.

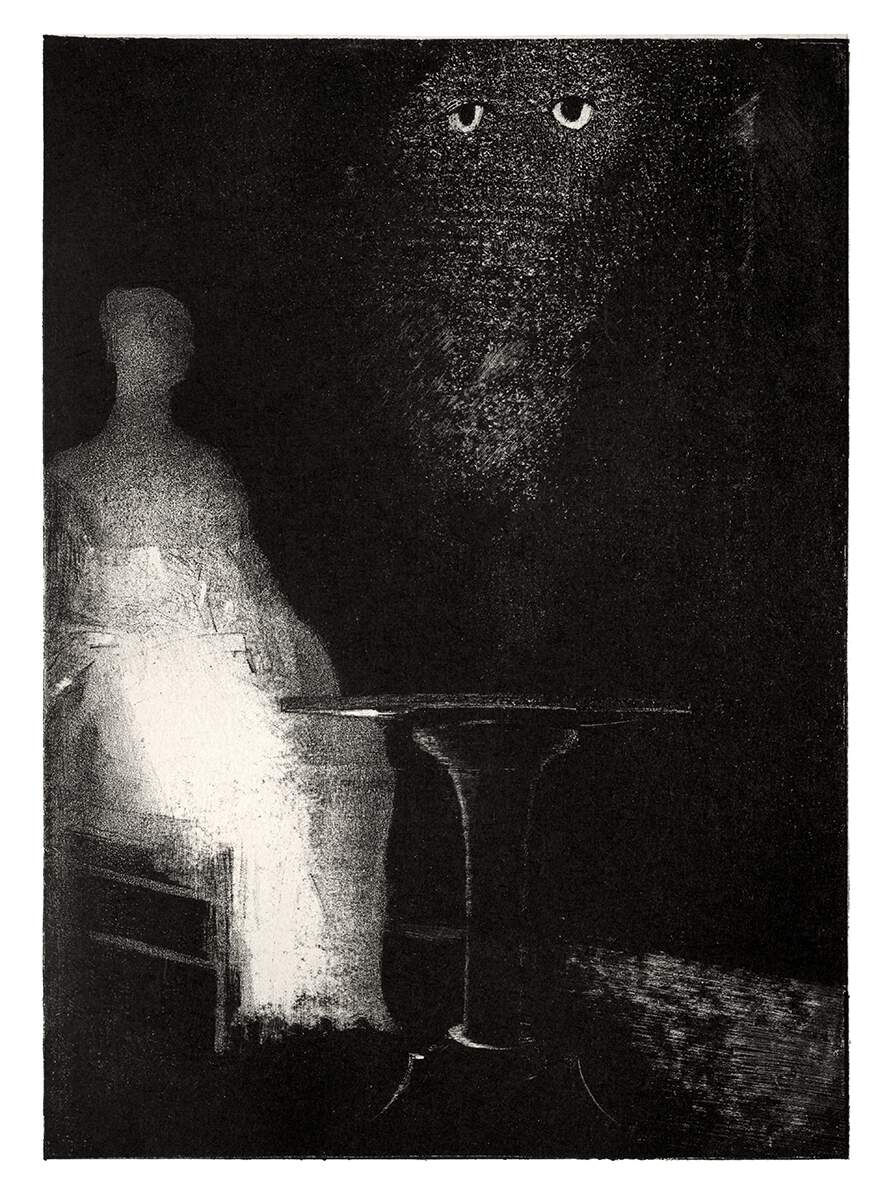

Sometimes we shape ourselves so carefully, craft personas to survive work, school, family, relationships, that we forget who stands beneath the scaffolding. We realise the performance has gone on too long, that the mask has grown skin. I've caught glimpses of myself in windows late at night, when reflection slips into resemblance. I walk past glass and see a man who looks like me – cleaner, more composed – he has answers, knows what to say, never stumbles in company. He is fluent in ease, and I, in the quiet echo behind him, feel like a stutter. This doppelgänger moves through the world with certainty while I trail behind, collecting fragments of authenticity like loose coins. In childhood, this division wasn't yet complete: I remember running through summer fields and parks, my shadow a perfect twin, neither leading nor following. Now the glass between us grows thicker. Sometimes I press my palm against the cold surface, wondering if the other me feels the pressure from his side, if he too lies awake wondering which of us came first, which is the original and which the invention. Perhaps we are both copies of something long vanished, like those faded photographs in old albums where the subjects' names have been forgotten but their eyes still ask to be recognised.

There is a concept in psychoanalysis – Jacques Lacan's 'mirror stage' – in which the child first recognises itself in the mirror and misrecognises what it sees as complete. This illusion of wholeness, of mastery, is seductive. It becomes the image one chases after. But it is always already a fiction. What we see is not what we are, only what we hope to become. In that unsavoury sense, Richard is all of us, performing completeness to make up for a splintered core. The danger, of course, is when you start to believe the reflection, when the glass becomes not a boundary but a blueprint for the self you're frantically assembling from borrowed parts.

I think back to moments where I over-performed myself, where I became a more palatable version of my own interior: sharper in wit, cleaner in sentiment, smoother in gesture. I was often praised for it, encouraged, liked, admired (or not, sometimes). But afterwards, in private, I would feel something brittle beneath the skin, a fatigue deeper than tiredness, as if I had overwritten my own voice in the effort to be legible to others. This exhaustion had a texture, like paper worn thin at the creases, or like the strange hollowness that follows applause when everyone has left the room. Sometimes I would catch myself rehearsing gestures before entering a crowded space, as if my body were a sentence that needed editing before it could be read aloud.

Richard, in Shakespeare's hands, is terrifying precisely because he is so knowable. He confesses everything, lays his motives bare, and yet we continue to watch him ascend. He seduces us into complicity. But that seduction is also a cry for recognition. To play a role too well is to disappear into it. By the end of the play, Richard is a man haunted by the image he once constructed to gain power, and the ghosts of those who saw through it too late. I wonder how many of us live that way, constructing personas so finely tuned to social survival that we end up estranged from our own sense of self. We become trusted colleagues, romantic partners, sons, daughters, mentors, performers. We curate and charm, and smile easily, and when we are alone, the lights go out, the stage empties, the mask slips, and we're left staring into a mirror we forgot to polish, seeing a face we no longer quite recognise as our own.

It's not that the performance is false. Often, it's based on something true. But it becomes truth's echo, stretched too thin. Richard's deformity is famously ambiguous in Shakespeare's play: he speaks of his misshapen body, but we never truly see it. It becomes a metaphor for internal deviation. A reason, an excuse, a shield. He uses it to explain his cruelty, to distance himself from softness, to pre-empt rejection with control. In that, I recognise something familiar: the armour of irony, the deflection of earnestness. The pre-emptive self-mocking that says, "I already know what you're thinking, so you can't wound me with it." It's not malicious. It's protective. But like Richard, it can calcify. The distance we create becomes a room we cannot leave, a prison built of our own defensive architecture, with windows that only look outward, never in.

I've had moments – sharp, clear ones – where someone looked at me and saw, momentarily, through the scaffolding. They paused. Their expression changed. They asked, gently, if I was okay. And in that instant, I felt exposed and grateful and terrified all at once. Because to be seen without the mask is both a kind of freedom and a kind of loss. It means giving up control of the narrative. Richard cannot do that. He dies clutching the remnants of his image. "A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!" Not a final confession, but a last, desperate attempt to survive. There is no true unmasking. Only the mask slipping too far to function, revealing not the authentic self but the terror of its absence.

But theatre offers another kind of mirror. The stage, for all its artifice, can become a space of revelation. A place where masks are worn in order to be removed. Where performance is not deception, but exposure. I've often found more truth in a well-crafted soliloquy than in hours of conversation. Perhaps because it dares to say what we all conceal. In that way, Richard's tragedy isn't just that he's evil. It's that he believes he must be. That the role he was cast in – by others, by circumstance, or his own fear – must be played through to its bitter end. There's no room in his world for softness, vulnerability, or change. And so, he becomes the villain because he cannot imagine another script. The tragedy deepens when we recognise how many of us live this way, trapped in characters we've outgrown but cannot bear to abandon. I think we all have moments where we fear that the role we’ve played is the only one available to us. That if we stop smiling, stop pleasing, stop controlling the story, we will vanish. But the truth is quieter, and more difficult. The truth is that we remain, even when the lights go out. The person beneath the role is not empty, but waiting.

When I think of mirrors now, I don't think of Lacan or Richard. I think of the old dressing rooms in theatres. Flickering bulbs around the frame, smudged glass, a chair slightly askew. A space where actors become characters and characters become confessions. I imagine someone sitting there, alone after the show, wiping off makeup, watching the echo of their performance dissolve into something quieter: breath, a face, the beginning of something. It has taken me years to unlearn the compulsion to perform. Not to abandon it entirely (performance can be beautiful and connective and necessary), but to stop believing it's the only way to be seen. I'm learning to speak without rehearsing, to enter rooms without armour, to let silence sit beside me without apology.

Sometimes I still feel the old reflex: the urge to smooth, to dazzle, or over-articulate. The practiced laugh that rises before I've felt anything funny. The way my hands arrange themselves in gestures I've seen work before. The voice that modulates to fill whatever emotional vacancy seems most urgent in the room. But then I remember Richard, standing in his broken hall of mirrors, lost among the versions of himself he built to survive. And I remember the quieter self, the one who waited, watched, endured through all those performances; the self who kept vigil while I exhausted myself with becoming. And I choose him.

References

Shakespeare, William. Richard III.

Lacan, Jacques. “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I” in Écrits.

Brook, Peter. The Empty Space.